Table of Contents

What is an Epigastric Hernia?

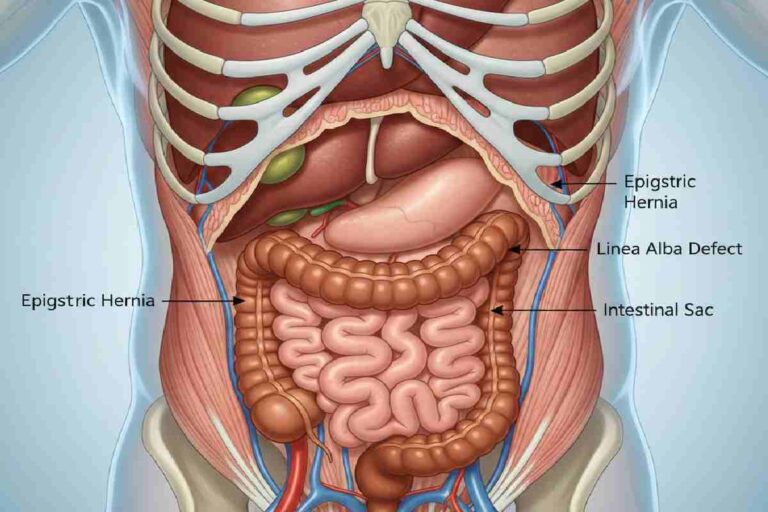

An epigastric hernia is where the fatty tissue or intestine shifts through a degree of weakness in the linea alba, the connecting tissue band. Which runs along the front of the abdomen between the breastbone (sternum) and belly button. These hernias are minor usually less than 0.5 inches but may enlarge with the passage of time. They cause 2-3 percent of abdominal hernias and can therefore be overlooked because they have very minimal symptoms.

Epigastric hernias occur higher and they may be multiple in 20% of cases unlike umbilical hernias at the navel. They can be either congenital or acquired due to muscle weakness.

Symptoms and Signs

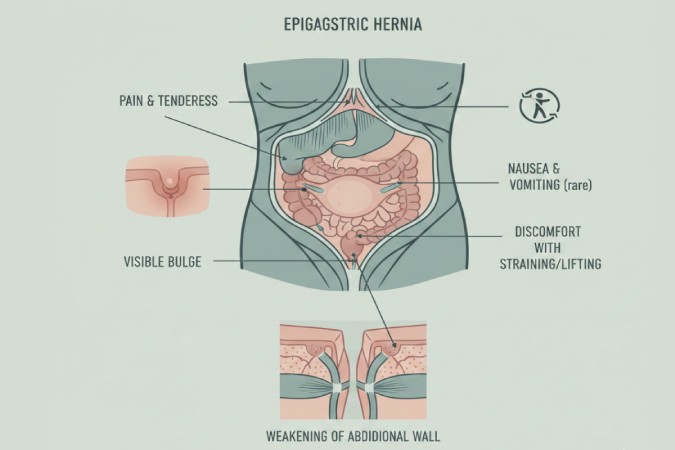

Lots of hernias of the epigastric type do not give symptoms, particularly the small hernias. The presence is characterized by the presence of a visible or palpable upper abdominal bulge which can occur in coughing, straining or standing. Pain is dull and sharp tenderness, which is aggravated by activity.Other indicators:

- Redness or tenderness at the site.

- Painful bulge on coughing (impulse on cough).

- Rarely, nausea if bowel involvement occurs.

Seek immediate care for severe pain, vomiting, fever, or unyielding bulge, signaling possible incarceration or strangulation.

Causes and Risk Factors

Weak abdominal muscles allow intra-abdominal contents to protrude through linea alba defects. Congenital gaps from fetal development contribute, but acquired cases dominate in adults aged 30-50.

Key risk factors:

- Obesity increases abdominal pressure.

- Pregnancy, heavy lifting, or chronic coughing strains the wall.

- Aging, genetic defects, or severe vomiting weaken tissues.

Global prevalence data shows abdominal hernias affected 6.75 million people in 2021, with epigastric types common in middle-aged men and obese individuals.

| Risk Factor | Impact on Hernia Development |

| Obesity | Elevates intra-abdominal pressure |

| Heavy Lifting | Strains linea alba repeatedly |

| Pregnancy | Stretches abdominal muscles |

| Chronic Cough | Causes persistent pressure |

| Aging | Leads to natural muscle weakening |

Diagnosis Methods

An epigastric hernia is first diagnosed with a physical examination where your doctor examines the upper abdomen to identify a bulge or tenderness, and he/she may have you cough, strain, or stand so that the defect is more distinct- he/she may actually feel the hernial orifice itself.

Key Tests

Ultrasound is the most important imaging method with real-time images of the size, location, and contents (fat or bowel) of the hernia and the exclusion of other defects of the midline such as rectus diastasia.

For complex cases:

CT scan provides detailed cross-sections (complications of surgical planning), sometimes using contrast dye.

Improved soft-tissue imaging MRI offers better soft-tissue imaging when ultrasound is inconclusive, but is less frequent.

Routine blood tests are not required unless some complications such as infection are suspected. These tests are used to make an early diagnosis to direct watchful waiting or early surgery.

Treatment Options

Watchful waiting suits asymptomatic small hernias with regular monitoring. Surgery is the definitive fix for painful or enlarging ones, as they won’t resolve naturally.

Procedures:

- Open repair: Incision over hernia, fat/intestine repositioned, defect stitched or meshed (30 minutes under general anesthesia).

- Laparoscopic: Minimally invasive with mesh for lower recurrence.

Mesh reduces recurrence vs. sutures alone, per systematic reviews. Post-op recovery: 1-2 weeks for light activities, 4-6 weeks avoiding heavy lifts.

Pros and cons of surgery:

| Approach | Pros | Cons |

| Open Repair | Simple for small hernias | Larger scar, higher infection risk |

| Laparoscopic | Faster recovery, less pain | Requires expertise, costlier |

| Watchful Waiting | No intervention needed | Risk of enlargement/complications |

Complications and When to Worry

Hernias are dangerous to become incarcerated (stuck contents) or strangled (blood supply cut), which leads to bowel obstruction, which is a medical emergency with fever, vomiting, extreme pain.

Risks of surgery: infection (1-5 percent), recurrence (low with mesh) bleeding, or mesh problems. New statistics are stressing immediate repair in order to prevent them.

Prevention Strategies

Keep the weight healthy to decrease pressure. Do not lift a lot of weight or use correct technique (bend knees). Firm through yoga or planks, but make consultation with the doctors after diagnosis. Control coughs and constipation.

An Experience with Epigastric Hernia.

Asymptomatic cases can be managed with normal life. The symptomatic ones affect the daily activities until they are fixed. Nutrition is helpful: straining prevented by high-fiber food.

Conclusion:

An epigastric hernia is a common abdominal wall defect causing a bulge between breastbone and belly button, often painless but treatable via surgery if symptomatic. Risk factors include obesity and strain; complications like incarceration are rare but serious.

FAQ Section

What causes an epigastric hernia bulge to appear suddenly?

Straining like coughing or lifting pushes fat through the weak spot; it may reduce lying down.

Is epigastric hernia surgery outpatient?

Yes, most return home same day with 1-2 weeks light duty.

Can epigastric hernias resolve without surgery?

No, they persist but may stay asymptomatic; surgery cures.

How common are epigastric hernias in adults?

2-3% of abdominal hernias, often underreported.

Does obesity directly cause epigastric hernia?

It increases risk via pressure; weight loss helps prevent.